Monarch Habitat Preservation

The miraculous migration of Monarch butterflies reminds us of the importance of the restoration and preservation of monarch habitat. Without proper habitat for each stage of its life cycle, Monarchs cannot make their remarkable generational journey back to a few acres to survive winter.

Migration of the Monarch:

Monarch migration is one of nature’s great wonders. It is difficult to comprehend that such a small insect can travel thousands of miles, but it is truly staggering to consider that no single individual completes the entire migration. It takes up to four generations of Monarchs to complete the annual migration. Preserving and restoring Monarch habitat all along this route for each generation is mandatory if we are to ensure healthy populations of Monarch thrive.

When a Monarch leaves the overwintering grounds in Mexico, it will typically reach the southern United States to reproduce and die. The second generation will continue to travel north, perhaps as far as the Canadian border, where it will reproduce and die. The third generation will begin the journey south, reaching the Mid-Atlantic states where it will reproduce and die. The fourth generation of Monarchs is typically the generation that makes the epic journey of thousands of miles back to their traditional overwintering grounds in Mexico.

Monarchs that live west of the Rocky Mountains have different migration patterns. Their overwintering grounds are found in California. There are more than 300 identified overwintering grounds in California, many of which are at risk of habitat destruction. Their population peaks in November and December. By January, the Monarchs in California begin to migrate in search of suitable mating habitat.

Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve:

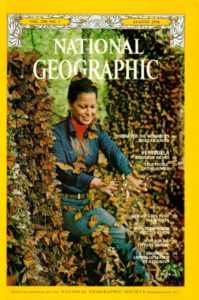

The overwintering grounds in Central Mexico were only ‘found’ in the mid-1970’s by biologists in the United States. The August 1976 cover of National Geographic declared “Discovered: The Monarch Mexican Haven”. Of course, the discovery came with the aid of indigenous people in the region who had long known the Monarch’s secret.

Soon after the disclosure of the Monarch’s overwintering ground, the Mexican government began establishing the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve to preserve the Monarch habitat. This habitat is Oyamel fir forests on mountainsides about 65 miles northwest of Mexico City. The reserve protects eight known colonies of Monarchs.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has listed the Monarch Reserve on the World Heritage List noting that the “overwintering concentration of the monarch butterfly in the property is the most dramatic manifestation of the phenomenon of insect migration” and that this overwintering population in such concentrated areas “is a superlative natural phenomenon.”

Monarch Reserve is on UNESCO’s World Heritage List

Fortunately, the Mexican government had the wisdom to protect far more land than just the tiny footprint of locations in which Monarchs actually overwinter. The Monarch Reserve covers roughly 140,000 acres. But Monarchs historically have covered only about 15 to 20 acres of the reserve. However, the remaining acreage is forest land that helps protect the Monarch as they overwinter, especially from extreme weather including cold snaps.

This Monarch is nectaring from a Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). A close look at its head will reveal two antenna and a proboscis. The proboscis is used to extract nectar from the flower. In this photo the proboscis is bent at a 90 degree angle and is probing the flower for nectar. Photo courtesy of Andi Pupke.

Regrettably, threats to the Monarch habitat remain even in the Biosphere Reserve. Much of the land within the reserve is still in private ownership. Logging remains a lethal threat to Monarchs. The logging comes from timber interests, drug cartels, and local indigenous residents. Crime in the region is rampant, exacerbating efforts to protect the reserve.

Unfortunately, the U.S. State Department just last month issued a “Level 4: Do Not Travel Advisory” for the state of Michoacán where most of the Monarch Reserve is located. This advisory is due to the high level of crime in the area and is an indicator of the threat the Monarch’s overwintering habitat faces despite the governmental protections placed on the region.

Monarch Butterfly Life Cycle:

Monarchs provide an excellent example of complete metamorphosis. This includes four stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. The egg is self-explanatory. It is a small sphere about 1 millimeter in circumference typically laid on the underside of a milkweed plant. A Monarch may lay anywhere from 300 to 1,100 eggs in its brief life.

The larva is the caterpillar that hatches from the egg. The caterpillar goes through five stages of growth called instars. Each instar is slightly different in appearance and progressively larger. At the end of each instar, the caterpillar molts (sheds its skin). The classic look of a Monarch caterpillar develops during the second instar. This look includes white, yellow and black bands.

The final instar molts and transforms into the chrysalis. Immediately before this final molt, the caterpillar spins a silk pad to hang itself from during this pupa stage. A chrysalis is not a cocoon — a cocoon is the pupa stage of a moth while the chrysalis is the pupa stage for a butterfly. While the Monarch is encased in its beautiful chrysalis, the adult butterfly develops.

The adult Monarch is one of the most easily recognized butterflies in the world.

Its orange and black coloring makes it easy to spot. The adults in most generations live about two to five weeks. But one generation will live much longer.

Monarchs mating. Monarchs undergo complete metamorphosis. After mating, the female lays an egg. The egg hatches and becomes a caterpillar (larvae stage). The caterpillar transforms into a chrysalis (pupa stage). The butterfly (adult) emerges from the chrysalis. Photo courtesy of Andi Pupke.

Monarchs have special habitat requirements during the various stages of the life cycle. The eggs are typically laid on milkweed plants because the caterpillars eat milkweed exclusively. The adults feed on nectar for a wide variety of flowers and good Monarch habitat must have flowering milkweed plants throughout the summer and into the fall. Overwintering Monarchs have very specific habitat needs without which an entire population could be lost. Preserving and restoring Monarch habitat for each of its life cycles is critical to their survival.

Milkweed and Toxins:

Planting milkweed is a critical step in restoring Monarch habitat. Common Milkweed is especially important because it contains high concentrations of cardenolides, a toxic steroid that gives the Monarch a bitter taste. This bitter taste helps protect the Monarch’s caterpillar and butterfly from predation. This protection helps explain why this insect is so brightly colored — Monarchs want to remind predators that they are toxic.

This Monarch caterpillar is eating the seed pod of Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa). Although in the milkweed family, Butterfly Weed does not have as beneficial impact on Monarch caterpillars as Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). Common Milkweed has higher amounts of the toxin (cardenolide) that makes the Monarch bitter tasting. Photo courtesy of Chris Pupke.

This strategy is so successful that one butterfly has developed to mimic the Monarch. The Viceroy is also orange and black, but it is slightly smaller and has an extra circular band on its hind wings. This band, according to some, makes it appear as though the Viceroy is smiling at them.

Planting milkweed is a fundamental component to restoring Monarch habitat.

The Monarch’s reliance on milkweed cannot be overstated. Monarch Watch estimates that up to 80 million acres of monarch habitat have been lost to modern agriculture practices including the adoption of herbicide resistant crops. Fortunately, that trend is slowly reversing itself as concerned individuals dedicate themselves to restoring Monarch habitat by planting milkweed.

The critical value of milkweed to Monarch is well known but less well understood. When planting milkweed for Monarchs in the east, one must focus on planting Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), not other species of milkweed. Common Milkweed contains higher concentrations of the toxic steroid that help Monarchs develop that bitter taste that makes predators want to avoid them.

Focus on planting Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) for good Monarch habitat

Viceroy butterflies mimic the bright coloration of Monarchs in an effort to fool predators. The semi-circular band (which looks like the smile of someone fooling someone…) helps identify the Viceroy. Photo courtesy of Chris Pupke.

However, restoring Monarch habitat requires more than just planting milkweed. We must also consider the needs of the adult monarch. Fall nectaring flowers are vital for migrating Monarchs and preserving their overwintering habitat is crucial.

Related Blog by Chris Pupke: Dragonflies — Important Environmental Indicators

The August 1976 cover of National Geographic helped the world learn about the Monarch’s secret Mexico overwintering grounds.

Tagging Monarchs:

Tagging Monarchs helps scientists learn about their migration habitats. This information is particularly important for the preservation of Monarch habitat without which these butterflies would not survive their epic migration.

Volunteers carefully catch Monarchs in butterfly nets. A small tag is placed on the underside of its wing. This tag does not interfere with the Monarch flight abilities. It contains a simple identifying number usually consisting of 3 letters and 3 number (i.e.: ABC123) and an email address.

Each tag is registered by the tagger. The information includes the tag number, location of the tagging, the name of the tagger, and the sex of the butterfly. This information is then returned to the coordinating organization. If a tag is recovered, it is reported back by email.

Monarch Watch runs the largest tagging program with citizen scientists.

A tagged Monarch prepares to venture south from Maryland to Mexico by nectaring on a Maximillian Sunflower (Helianthus maxiilliani). Monarchs need fall nectar sources to survive their arduous migration.

Tagging Monarchs provide a slew of information that allows us to better understand Monarch habits. They note that tagging “helps answer questions about the origins of monarchs that reach Mexico, the timing and pace of the migration, mortality during the migration, and changes in geographic distribution.” This data will help conservationists plan additional habitat preservation and restoration projects to benefit Monarchs.

Related Blog: Endangered Species Act Remains Endangered by Dr. Richard Pritzlaff

Monarch Habitat Preservation and Restoration:

Preserving and restoring Monarch habitat is vital for the survival of these remarkable insects. Planting milkweed for caterpillars and nectaring plants for adults will provide Monarchs with food sources during the various stages of their life cycles. Furthermore, the preservation of their overwintering grounds in Mexico (and California!) is critical.

Unfortunately, population trends are not good for Monarchs. The standard method to determine Monarch population is the number of acres covered in their overwintering grounds. From 1993 to 2003, Monarchs typically covered about 15 to 20 acres in their overwintering grounds in Mexico. This included a high of 45 acres in 1996 and a low of 9.5 acres in 2000.

In recent years, the population has declined markedly. Since 2009, the annual acreage covered by Monarchs each winter averages 5.8 acres. The high population count found 9.93 acres in 2010. The low covered a devasting 1.66 acres in 2013. The overwintering population during the winter of 2017-18 covered 6.12 acres.

Monarchs face many threats, including predation from other insects such as this praying mantis. However, the biggest threat Monarch face is loss of habitat.

Preservation of Monarch Habitat has never been more important…

With their declining population the work of preserving and restoring Monarch habitat has never been more important. Plant milkweed — but don’t forget to also plant fall flowering plants to provide nectar sources for migrating Monarchs. Do not mow meadows until after the fall migration ends. And, advocate for improved protections to Monarch habitat from Mexico to California and Texas to New York and even at your local county park.

Biophilia Foundation’s commitment to support habitat preservation and restoration on private lands helps Monarch butterflies.

For example, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage (CWH) works to plant meadows that provide excellent habitat for migrating Monarchs. CWH also conducts annual tagging programs to help researchers learn about Monarch migration patterns and habitat needs. Borderlands Restoration is selling native milkweed to ranchers and homeowners in Southern Arizona. Another partner, Wildlands Network, works to ensure all that life in all its diversity can thrive directly benefits a host of wildlife including Monarchs. And as an added benefit, when we preserve and restore habitat for Monarchs, we also help other species of wildlife like butterflies, birds, pollinators and more!

A word of thanks to my wife, Andi Pupke, a wildlife biologist at Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, whose decades of work restoring Monarch habitat, researching their migration patterns, and educating the public about their plight informed and, more importantly, inspired this blog.

Tagging Monarchs provides important information about their migration patterns. A small tag is placed on their underwing. The tag information is recorded and sent to Monarch Watch. The recovered data can help conservationists plan preservation and restoration projects for Monarch Butterfly habitat. Photo courtesy of Andi Pupke.

Related Blog: Horseshoe Crabs and Relationships Are Worth Working On

Sources:

https://www.fws.gov/midwest/monarch/overwinteringmonarchs.html

https://www.fws.gov/savethemonarch/

Halpern, Sue; Four Wings and A Prayer; Pantheon Books, New York; 2001.

Marriott, David; “Where To See Monarchs In California”; Monarch Program, California Monarch Studies; 1997.

https://www.monarch-butterfly.com/ [This site has a set of excellent photos showing the caterpillar becoming a chrysalis and the chrysalis becoming an adult butterfly.]

https://monarchlab.org/biology-and-research/biology-and-natural-history/breeding-life-cycle/interactions-with-milkweed/

https://www.monarchwatch.org/tagmig/ [This site has a map that shows the overall generational migration pattern of adult Monarchs.]

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/m/monarch-butterfly/

“Native Habitats for Monarch Butterflies in Southern Florida”; Frank Mazzotti et al; University of Florida, Institute of Agricultural and Food Services; WEC266; Revised March 2012 and Reviewed June 2018.

Schappert, Phil; The Last Monarch Butterfly; Firefly Books; Buffalo, NY; 2004.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1290

Recent Comments