Wildlife Friendly Fencing

Wildlife friendly fencing presents an alternative to standard livestock fencing

Livestock fencing can present a significant hazard to wildlife. It can disrupt migration, separate herds and even kill wildlife. Fortunately, wildlife friendly fencing presents an alternative that helps contain livestock while also not presenting a mortal threat to wildlife.

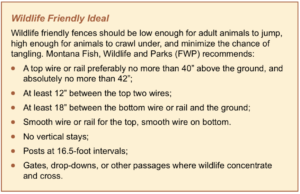

Some of the specifics of wildlife friendly fencing are relatively straightforward. The top wire should be no higher than 40 inches above the ground. The bottom should be at least 18 inches above the ground. Both top and bottom wires should be barbless. These basic guidelines (there are more guidelines that should be followed below) will help alleviate conflicts wildlife might have with a fence. A fence designed like this will give animals a much better chance to get over or under it.

But these figures do not tell the story of why –why we need more ranchers to adopt wildlife friendly fencing on their pastures.

Why we need more ranchers to adopt wildlife friendly fencing…

To learn more about the need for wildlife fencing, one simply needs to picture the image of a dead fawn curled up alongside a fence. To these fawns, a livestock fence is a deadly barrier that prevents an otherwise young and healthy animal from traveling on with its mother. It cannot do anything but wait, hope, and lay by the fence while slowly starving.

This is not an unusual problem. For example, a study conducted in 2006 by Utah State University found an average of one dead ungulate lying next to fencing every 1.2 miles and 90% of those fatalities were fawns. The study covered 600 miles for one year–so that means more than 400 healthy fawns died waiting for an opening in the fence in one year along those 600 miles of fencing alone.

Related blog post: Undeveloping for Wildlife

‘Unfriendly’ wildlife fencing causes injury to animals

Standard livestock fencing does not just take the lives of young fawns. Healthy adults can get tangled in the wires. Sometimes the antlers get tangled and the animal struggles for a long period-of-time trying to break free. Sometimes one of their legs gets caught and they are unable to move off the fence –this is especially common with woven wire fences (the type that looks like a grid.)

Livestock fences present a real issue for wildlife – that 2006 study by Utah State found mortality rates of ungulates entangled in fences at one ungulate per 2.5 miles. This study was conducted in northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado. Healthy, young juveniles were eight times more likely to be killed in the fences – making this problem particularly impactful.

And it’s not just mammals. A 2009 University of Idaho/Idaho State study of Sage Grouse in Idaho found 36 Sage Grouse, 24 unknown and 2 Western Meadowlark fatalities along 66 kilometers of fence rows –nearly a 1 fatality per kilometer rate.

The USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service notes:

“Fencing used to define property boundaries and contain livestock creates barriers and traps to wildlife movement, fragments habitats, and separate herds. Improper fence design results in injury and death through entanglement and collision. Wildlife friendly fencing techniques allow for safe passage and increase fence visibility improving wildlife habitat, granting access to food, shelter, and water.” USDA NRCS: ANM27; 2014

Related article — Wood Ducks: A Cautionary Tale With a Happy Ending?

Properly designed, installed, and maintained livestock fences can save wildlife.

According to Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, properly designed fencing for wildlife has the following characteristics:

1) Top wire is no more than 40 inches high;

2) Bottom wire is no lower than 18 inches;

3) Contains a gap of at least 12 inches between top two strands;

4) Contains a smooth wire or rail for the top;

5) Contains a smooth wire for the bottom; and

6) Be visible.

Biophilia Foundation is proud to support a partnership that is seeking to address the menace that livestock fences pose to wildlife. Wild Utah Project and Yellowstone to Uintas Connection forged the partnership.

Wild Utah Project “strives to provide non-profit partners and public agencies with the best available and up-to-date science to advance conservation across Utah.” Yellowstone to Uintas Connection is “working to restore fish and wildlife habitat in the Yellowstone to Uintas Corridor through the application of science, education, and advocacy.”

A critical 350-mile wildlife corridor to be protected with wildlife friendly fencing

They are working to protect a critical 350-mile wildlife corridor between Yellowstone National Park and the Uintas Mountain Wilderness in northern Utah. The non-profits are currently identifying key wildlife movement impedance points created by fencing on private parcels in the Bear River Range.

The Bear River Range is a key component of Wildlands Network’s Western Wildway. Wildlands Network is another Biophilia Foundation partner. Their Western Wildway seeks to “establish a contiguous network of private and public conservation lands along the spine of the Rocky Mountains and associated ranges, basins, plateau, and deserts from Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental to Alaska’s Brooks Range.”

Wildlife friendly fencing is just one of the ways that Biophilia Foundation works to help wildlife. We invite you to show your connection with and compassion for the natural world by helping wildlife. Some easy ways you can do this is by planting a pollinator garden or feeding birds. More complicated for example is restoring a wetland. For the more complex we could use your help funding the experts on the ground doing this critical work. 100% of what you donate to Biophilia Foundation goes to funding our partners in wildlife conservation who are carefully chosen for funding.

Specifications for wildlife friendly fences per Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Sources:

Wild Utah Project: https://www.wildutahproject.org/projects/

Wildlands Network: https://wildlandsnetwork.org/wildways/western/wildlife-corridors/

Yellowstone to Uintas Connection: https://yellowstoneuintas.org/about-us/mission-vision

Recent Comments